Scientists to explore mysterious Lake Huron sinkholes

Research boat explores a sinkhole on the northern edge of Rockport’s Middle Island. Image: NOAA/David Ruck, Great Lakes Outreach Media

By Carin Tunney

Scientists will return to Lake Huron this summer to explore one of the deepest mysteries of the Great Lakes – underwater sinkholes.

Lake Huron sits on a layer of 400-million-year-old limestone – the remnants of an ancient seabed. Groundwater runs vertically under the lake and pushes through the limestone, making deep, underwater sinkholes, said Steve Ruberg, a researcher with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory, which leads the research that begins this August. The project includes scientists from across Michigan and Wisconsin.

Much of the mystery involving the sinkholes relates to a unique “microbial community” that includes a type of cyanobacteria that live on sulfur and other bacteria. Cyanobacteria are one of the oldest organisms on Earth. They are notable for their ability to switch between oxygen and sulfur to produce the energy they need through photosynthesis.

The billions of years old cyanobacteria may hold the secret of how Earth went from inhabitable to habitable, sustaining plant and animal life.

Scientists with the Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary in Alpena, Michigan, first discovered deep depressions in the Great Lakes about 20 years ago while searching for shipwrecks. Advanced techniques to map underwater environments helped scientists identify the depressions as sinkholes. Scientists used to think sinkholes only existed in oceans.

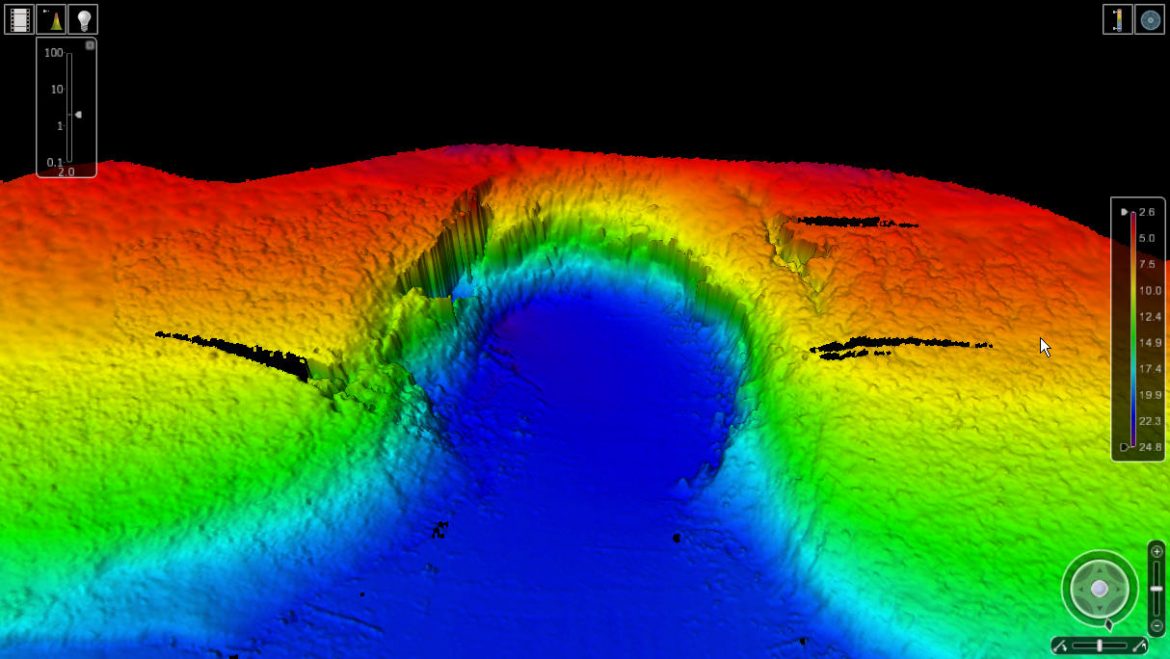

The sonar image shows the depth of the sinkhole. Blue represents 65 foot depth, while red and yellow indicate about 15 feet deep. Image: NOAA

There is a lot to learn about these underwater ecosystems, Ruberg said.

“When you look at the Great Lakes, we have a good understanding of ecosystems and how things work,” he said. “But the remarkable thing is how little of the bottom areas we have mapped and how little we understand.”

Scientists explore sinkholes with divers, multi-beam sonar and robotic vehicles. The sinkholes average about 330 feet in diameter.

They’ve retrieved samples from about 410 feet below the surface, but some sinkholes may be deeper, Ruberg said. There are both nearshore and offshore sinkholes. Previous research projects gathered water samples from one about 16 miles from the coastal community of Rockport, Michigan.

Researchers said exploring sinkholes may lead to the discovery of new organisms. The cyanobacteria found in offshore sinkholes have genetic markers only seen in the ocean off the coast of Africa. Those closer to the shore are matched to organisms found in ice-covered lakes in Antarctica.

“So, the mystery here is pretty incredible,” Ruberg said. “It wouldn’t be surprising if we found something, a microbe that had not been found anywhere else.”

Greg Dick, an associate professor of earth and environmental science at the University of Michigan, said the cyanobacteria may also hold secrets about early earth before plants and animals evolved. Cyanobacteria were the first organisms to produce oxygen and make life on earth possible.

“We are hoping to learn what controls oxygen production systems with hope of understanding how that might inform our knowledge about how this earth became what it is, how it became habitable,” he said.

Dick also studies the relationship between the cyanobacteria and other organisms that form extremely rare “carpets of microbes” that look like dense purple mats inside the sinkholes. He said the mats may explain why oxygen production is limited to earth.

Microbial mats made of cyanobacteria and other organisms may hold answers about life on earth. Image: Phil Hartmeyer/Thunder Bay Marine Sanctuary

“The big picture thing is that we have this really extreme and unique environment right here in our backyard in our Great Lakes,” Dick said. “I think that these mats rival ecosystems like Yellowstone National Park and ice-covered lakes in Antarctica. So, for me, I’ve spent my career going to the bottom of the ocean and all over the world, and it’s really exciting to have these environments right in our Great Lakes.”

Another unique quality of cyanobacteria is that it can potentially be combined with antibodies to make pharmaceuticals, said David Sherman, a researcher with the University of Michigan’s Life Science Institute.

“We can tell a lot of the capabilities are to make certain types of biologically active peptides, so these are very simple proteins,” Sherman said. “These smaller peptides are often very biologically active, and the one that is currently FDA-approved that comes with the cyanobacteria is used for a cancer agent … the peptide is what kills the cancer cells, the antibody is like a guided missile that attaches to the cancer cells.”

Scientists also study how groundwater pushing up from sinkholes influences Great Lakes water levels. Ruberg said it’s another aspect of sinkholes that is not well understood and could have a small effect on lake levels.

Great Lakes Outreach Media produced a short film earlier this year that highlights the fieldwork involved in sinkhole research.